After great pain, what would the body learn

that it does not already know of relief?

When that fire-truck has raged past,

what do I rediscover about silence,

except that I would always miss it?

Do trees mind if it is the same wind

that passes through their heads everyday?

After the mall is completed, must we

remember the field it inhabits now

where we chased each other as children?

If my lover fails to wake me with a kiss

a third time this week, do I worry?

After the earthquake, would it matter if

no one saw two dogs from different

families approach each other

without suspicion, then move apart?

As the workers wash their faces hidden

by helmets that beam back the sun,

should they care about the new building

behind them beyond the fear of it falling?

Does solitude offer strength over time,

or is denial of it the only practical aim?

If my mother cannot see how else

to be happy, is it enough that she may lie

in bed, convinced God watches her sleep?

After severe loss, what does the heart

learn that it has not already understood

about regret? When all light finally

forsakes a room, do we take the time

to interrogate the dark, and to what end?

(Published in Language for a New Century: Contemporary Poetry from the Middle East, Asia, and Beyond)

Friday, February 27, 2009

Bird

I was a bird that decided

that falling was better

than flying, as there was

nothing easier than letting

go, and my winged body

crashed against the earth’s

heavy door, pushing it

open to enter a void,

where, even then, I was

still plunging through

silence and darkness,

for so long that it began

to feel as if I could be

perfectly still, or coming

to a still, or coming

out of sleep with a bird

falling in my mind

through sunlight and air,

until it is no longer a bird

but a fistful of feathers,

then an indistinct shadow,

and then not even that.

(Forthcoming in Oneiros by Firstfruits in 2009)

that falling was better

than flying, as there was

nothing easier than letting

go, and my winged body

crashed against the earth’s

heavy door, pushing it

open to enter a void,

where, even then, I was

still plunging through

silence and darkness,

for so long that it began

to feel as if I could be

perfectly still, or coming

to a still, or coming

out of sleep with a bird

falling in my mind

through sunlight and air,

until it is no longer a bird

but a fistful of feathers,

then an indistinct shadow,

and then not even that.

(Forthcoming in Oneiros by Firstfruits in 2009)

The Affair

My father, a recent retiree, decided to have an affair with the broom. My mother never suspected a thing. She only wondered once, and only for a split second, if her husband was perhaps spending too much of his free time doing housework.

A few months into the affair, the broom asked him to marry her.

“I can’t. I already have a wife,” he replied. “But we can always have an affair.”

And they did. As my mother continued to work in the day, he would pull out the broom from the closet by her waist and dance her down the corridors of the house, her bristly dress sweeping erotically across the dusty marble.

He even told the broom how deeply he loved her. She would look at him for a long time after that and answer that she would never let him go.

One night, when my mother kissed him on his cheek, which she did every night before she slept, he realised that he had begun to miss her.

The following morning, he opened the door to the closet and said to the broom, knowing she never slept, “I must leave you. I must try to save my marriage.”

But the broom smiled at him with pity. “Too late for that, my dear,” she replied. “I am all you know now.”

She was right. My mother had become a total stranger to him, her eyes like the start of long corridors he could no longer see the other end of, while his heart turned into a closet which the broom moved into like her second home.

In the years to follow, the affair went on and he was able to conceal his guilt and his remorse. And my mother never suspected a thing.

(Published in Vox)

A few months into the affair, the broom asked him to marry her.

“I can’t. I already have a wife,” he replied. “But we can always have an affair.”

And they did. As my mother continued to work in the day, he would pull out the broom from the closet by her waist and dance her down the corridors of the house, her bristly dress sweeping erotically across the dusty marble.

He even told the broom how deeply he loved her. She would look at him for a long time after that and answer that she would never let him go.

One night, when my mother kissed him on his cheek, which she did every night before she slept, he realised that he had begun to miss her.

The following morning, he opened the door to the closet and said to the broom, knowing she never slept, “I must leave you. I must try to save my marriage.”

But the broom smiled at him with pity. “Too late for that, my dear,” she replied. “I am all you know now.”

She was right. My mother had become a total stranger to him, her eyes like the start of long corridors he could no longer see the other end of, while his heart turned into a closet which the broom moved into like her second home.

In the years to follow, the affair went on and he was able to conceal his guilt and his remorse. And my mother never suspected a thing.

(Published in Vox)

Novel

As the novel begins, we are impatient for the mistakes we expect him to make. What he will do when the phone rings, his estranged son on the far end repeating his name like a plea. He finally succumbs—we are meant to believe he had it in him all along—and the voice will carry him to a distant place within himself where love is possible. Before he arrives, he will resist, resentful; he must overturn, predictably, that age-old failure to forgive.

This is how the story must sail. A confined perception, an emotion held underwater for too long. His mistake. One that affects change, retrieves his anchor, unties the boat of his shortening life, and nudges it from the harbour.

This is what sustains us, that is, if it is enough for a time to penetrate moments not our own, to find regretfully familiar the hero’s limited vision, his isolation mirrored in the dim, unsung corners of our lives. By the time the novel is almost over, the revelation should not be easy. Even if the truth remains, that there is no truth, this too, is insight. In any case, clarity waits. An unwavering queue of errors to the day he blinks and every cloud has gone up in smoke like the years he has wasted, dissolving into rain.

And what about us? Have we made all the blunders we were supposed to make in this story that we did not write, but which had written itself to the moment that we stood before the door to our new home, in disbelief? Did a part of us believe, perhaps, that we deserved this? Our reward: an untold afterlife of minor trials and nothingness occurring over and over, where the mistakes we commit are no longer lamentable.

Not, I will continue to sleep with strangers so that I may forget myself. Not, If nobody loves me like this, there is no reason to love. We open the door and forget to hold hands. I touch your cheek as compensation. These small retrievals are all we need now. Darling, we have all we need.

(Published in Tinfish)

This is how the story must sail. A confined perception, an emotion held underwater for too long. His mistake. One that affects change, retrieves his anchor, unties the boat of his shortening life, and nudges it from the harbour.

This is what sustains us, that is, if it is enough for a time to penetrate moments not our own, to find regretfully familiar the hero’s limited vision, his isolation mirrored in the dim, unsung corners of our lives. By the time the novel is almost over, the revelation should not be easy. Even if the truth remains, that there is no truth, this too, is insight. In any case, clarity waits. An unwavering queue of errors to the day he blinks and every cloud has gone up in smoke like the years he has wasted, dissolving into rain.

And what about us? Have we made all the blunders we were supposed to make in this story that we did not write, but which had written itself to the moment that we stood before the door to our new home, in disbelief? Did a part of us believe, perhaps, that we deserved this? Our reward: an untold afterlife of minor trials and nothingness occurring over and over, where the mistakes we commit are no longer lamentable.

Not, I will continue to sleep with strangers so that I may forget myself. Not, If nobody loves me like this, there is no reason to love. We open the door and forget to hold hands. I touch your cheek as compensation. These small retrievals are all we need now. Darling, we have all we need.

(Published in Tinfish)

Divine Intervention

When I think about God, He comes as a disembodied

voice in a poem that asks, Where’re you this instant?

Carefully I answer, I’m struggling down the side

of a mountain; behind me, the past has lifted off

into cloud; before me, I’ve yet to see level ground.

Then I am asked, What’re the moments that may

help you continue? It is an easy one: Every time

my lover unzips my body to reveal its joy, or when music

creates an opening in the air for a burdened heart to fill.

Since you’ve come this far, He chides, why have you

suddenly stopped walking? Taking a deep breath,

I tell Him, This is because I want to keep dancing

upon the jagged rocks without any fear of falling

and curse at those stars blinking ridiculously above;

not caring if I’m cold, or if my voice receives no echo;

not caring if there's still much further I'll have to go.

(Published in Famous Reporter)

voice in a poem that asks, Where’re you this instant?

Carefully I answer, I’m struggling down the side

of a mountain; behind me, the past has lifted off

into cloud; before me, I’ve yet to see level ground.

Then I am asked, What’re the moments that may

help you continue? It is an easy one: Every time

my lover unzips my body to reveal its joy, or when music

creates an opening in the air for a burdened heart to fill.

Since you’ve come this far, He chides, why have you

suddenly stopped walking? Taking a deep breath,

I tell Him, This is because I want to keep dancing

upon the jagged rocks without any fear of falling

and curse at those stars blinking ridiculously above;

not caring if I’m cold, or if my voice receives no echo;

not caring if there's still much further I'll have to go.

(Published in Famous Reporter)

Hush

Silent again, we begin to hear

noises in our heads, swelling

to overwhelm the sound of our

breathing. If we are silent for

long enough, something would surface

from under the wind-troubled

faces of murky ponds

our minds have become.

All at once, ripples would flee

in a singular, outward direction-

these questions of guilt or blame.

Then what comes up for air

would be a different quiet

we keep drowning, pinning it

underwater in our pride until

its legs stop kicking.

Different because we may hear

the mirroring of fear and

a time-sharpened dependency

within it. Such a quiet we only

hear when we do not hear:

waking together, every meal,

sharing the same cab home.

Listen. Listen. My hand swims

into the bay area of your hand.

If we are silent for long enough,

we could start over.

(Published in Asheville Poetry Review)

noises in our heads, swelling

to overwhelm the sound of our

breathing. If we are silent for

long enough, something would surface

from under the wind-troubled

faces of murky ponds

our minds have become.

All at once, ripples would flee

in a singular, outward direction-

these questions of guilt or blame.

Then what comes up for air

would be a different quiet

we keep drowning, pinning it

underwater in our pride until

its legs stop kicking.

Different because we may hear

the mirroring of fear and

a time-sharpened dependency

within it. Such a quiet we only

hear when we do not hear:

waking together, every meal,

sharing the same cab home.

Listen. Listen. My hand swims

into the bay area of your hand.

If we are silent for long enough,

we could start over.

(Published in Asheville Poetry Review)

Landing

What death may be: a slow, close-to-weightless

tilt, like a burgeoning foetus turning

slightly in the womb. The engine starts a low

growl like a stomach, the aircraft hungry to

land, to devour the space between its

falling body and the ground, followed by

the slow lick of its wheels against the runway’s

belly: pressing down, then skating forward,

only to decelerate, a sensual slow-mo,

and the plane makes a sound

like the hugest sigh of relief.

The seatbelt sign blinks off for the final time.

We rise up from our seats like souls

from bodies, leaving bulky hand luggage

in the overhead compartments, then

begin a tense line down the aisle, awkwardly

smiling at each other, remaining few minutes

alive with all kinds of ambivalences,

or simply relief at having arrived, at long last,

in that no-time zone of a country

without a name except the ones we give it;

weeping, laughing, both at once.

(Published in South)

tilt, like a burgeoning foetus turning

slightly in the womb. The engine starts a low

growl like a stomach, the aircraft hungry to

land, to devour the space between its

falling body and the ground, followed by

the slow lick of its wheels against the runway’s

belly: pressing down, then skating forward,

only to decelerate, a sensual slow-mo,

and the plane makes a sound

like the hugest sigh of relief.

The seatbelt sign blinks off for the final time.

We rise up from our seats like souls

from bodies, leaving bulky hand luggage

in the overhead compartments, then

begin a tense line down the aisle, awkwardly

smiling at each other, remaining few minutes

alive with all kinds of ambivalences,

or simply relief at having arrived, at long last,

in that no-time zone of a country

without a name except the ones we give it;

weeping, laughing, both at once.

(Published in South)

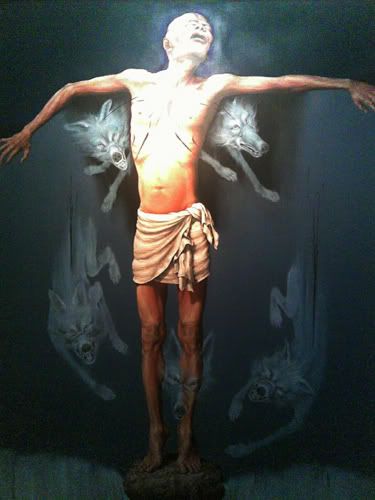

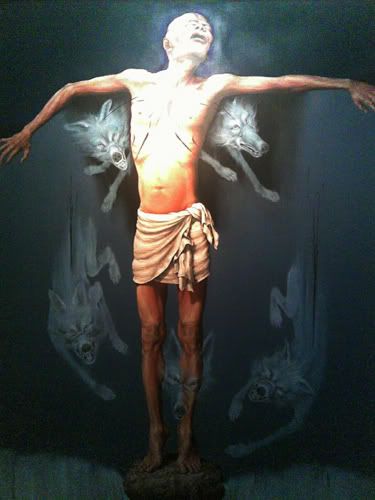

Interrogation

They asked the easy questions first,

like What is your name?

So I told them,

but they weren’t satisfied.

They wanted a different answer.

Who are you?

I hesitated, then said I didn’t know.

They laughed

and said they would torture me

if I didn’t improve.

Do you know why you are here?

Because I did something wrong,

I said. They asked me

what that was. I answered

it was because I didn’t know.

This time, they didn’t laugh.

I was more afraid

and began to tremble. You are

a poet? they asked.

I told them I didn’t know

what the word meant.

They grew angry. Suddenly,

I was calm. Their hands opened

and closed on the table.

What are your poems worth?

As much as your questions,

I replied.

Their eyes narrowed:

they would detach the skin

from my body, write

along its insides.

Do you know what we can do

to you? Yes,

I answered. And didn’t laugh.

(Published in Di-Verse-City and Force Majeure)

Painting inspired by the poem, "Interrogation," during the 2007 Utan Kayu Literary Biennale, held in Jakarta and Magelang, Indonesia.

like What is your name?

So I told them,

but they weren’t satisfied.

They wanted a different answer.

Who are you?

I hesitated, then said I didn’t know.

They laughed

and said they would torture me

if I didn’t improve.

Do you know why you are here?

Because I did something wrong,

I said. They asked me

what that was. I answered

it was because I didn’t know.

This time, they didn’t laugh.

I was more afraid

and began to tremble. You are

a poet? they asked.

I told them I didn’t know

what the word meant.

They grew angry. Suddenly,

I was calm. Their hands opened

and closed on the table.

What are your poems worth?

As much as your questions,

I replied.

Their eyes narrowed:

they would detach the skin

from my body, write

along its insides.

Do you know what we can do

to you? Yes,

I answered. And didn’t laugh.

(Published in Di-Verse-City and Force Majeure)

Painting inspired by the poem, "Interrogation," during the 2007 Utan Kayu Literary Biennale, held in Jakarta and Magelang, Indonesia.

Stepping into

the flat this evening,

something strange happened;

the veranda became a veranda,

the yellow lamp on the wall

a yellow lamp on the wall,

the mat on the floor turned red

instead of its present blue,

the woman who looked up

from the shelf of potted plants -

now a shelf of mangled bonsai -

became a woman with subtler lines

underneath her eyes, speaking,

as she had once spoken,

'Never forget.' I nodded,

as I had always nodded.

'I won't.' But that was then.

(Published in Poetry International)

something strange happened;

the veranda became a veranda,

the yellow lamp on the wall

a yellow lamp on the wall,

the mat on the floor turned red

instead of its present blue,

the woman who looked up

from the shelf of potted plants -

now a shelf of mangled bonsai -

became a woman with subtler lines

underneath her eyes, speaking,

as she had once spoken,

'Never forget.' I nodded,

as I had always nodded.

'I won't.' But that was then.

(Published in Poetry International)

Boats

You and your photographs of boats;

that repeated metaphor for departure,

or simply the possibility of a voyage?

What you cannot tell me you tell me

with a vessel and its single passenger,

eyes fixed on some skylit conclusion.

Set apart and starkly upon a canvas

of tractable waves, brought to still

by the trigger-click of your camera,

like the sound a key makes when it

releases the lock. Your heart became

that lock; these images how you have

always articulated distance, a withdrawal.

Darling, there are just as many ways

of saying goodbye as there are ways

of letting you go. The boat is narrow

like the width of my heart after

impossible loss, cruel resignation;

this heart you ride in. Love, if this is how

you choose to leave me let me let you.

(Published in Atlanta Review)

that repeated metaphor for departure,

or simply the possibility of a voyage?

What you cannot tell me you tell me

with a vessel and its single passenger,

eyes fixed on some skylit conclusion.

Set apart and starkly upon a canvas

of tractable waves, brought to still

by the trigger-click of your camera,

like the sound a key makes when it

releases the lock. Your heart became

that lock; these images how you have

always articulated distance, a withdrawal.

Darling, there are just as many ways

of saying goodbye as there are ways

of letting you go. The boat is narrow

like the width of my heart after

impossible loss, cruel resignation;

this heart you ride in. Love, if this is how

you choose to leave me let me let you.

(Published in Atlanta Review)

I Didn't Expect To Write About Sex

Did you know that after I came, I imagined my pelvis had emptied out into a dark cave you could crawl into, lay yourself down and fill my body with your sleep? This isn't really about sex, is it? Yet I could write about your tongue, how cleverly you rotated it like a key to slip open every lock of resistance under my skin, muscles loosening like a hundred doors creeping open across the conservative, suburban town of this flesh, desire stepping into the open like Meryl Streep in that film with Clint Eastwood, a wind calling forth the stiff body from under her dress so wholeheartedly how could she not help but undress, welcome it in. I could also write about your hands, tenacious dogs of your fingertips unearthing pleasure from every pore, jumpstarting nipples with the flick of your nails, each time you pushed in deeper from behind. I must not forget to write how much I love you when you warn me not to swallow; I love how I take you anyway into my mouth like tugging a recalcitrant child back into the house, even though he realizes deep inside himself that he would always long for home; I love how you taste, what was inside of you now inside of me, sliding down my throat like the sweetest secret. I could write about how when you fell off the peak of your mounting hunger, your hands stayed anchored upon my nape, as if to keep from drowning, as if to let me know, "Even when I'm this far gone, I'd want you here. I'd want you with me."

(Published in Chinese Erotic Poems)

(Published in Chinese Erotic Poems)

Aftermath

Take our cue from time, the master. Learn to weigh

everything equally: hope and grief, two sides

to a partner we should love unconditionally.

Learn to love a clean kitchen, as well as the ants

around the bin like the spoor of something

left unsaid, something important.

To love the illness, the perspective earned thereafter.

To try and love death; how heroic the attempt.

Then we fail, the hours pressed too thinly.

Mirrors draw out a cry from inside the womb

of a mind swollen with terror.

Then we stop to gather the pieces again. To love

the pieces as they are, scattered all around us.

But look at how we have been tempered,

the selves that wanted and kept wanting –

they just ask for more of the same now.

Let us not give the years too much credit

for how far we have come,

for what we have become.

To love the smell of rain, the cold rain on our faces.

Love the thunder and the sleep it cracks open.

What we have now. And what will come after.

(Published in Cider Press Review)

everything equally: hope and grief, two sides

to a partner we should love unconditionally.

Learn to love a clean kitchen, as well as the ants

around the bin like the spoor of something

left unsaid, something important.

To love the illness, the perspective earned thereafter.

To try and love death; how heroic the attempt.

Then we fail, the hours pressed too thinly.

Mirrors draw out a cry from inside the womb

of a mind swollen with terror.

Then we stop to gather the pieces again. To love

the pieces as they are, scattered all around us.

But look at how we have been tempered,

the selves that wanted and kept wanting –

they just ask for more of the same now.

Let us not give the years too much credit

for how far we have come,

for what we have become.

To love the smell of rain, the cold rain on our faces.

Love the thunder and the sleep it cracks open.

What we have now. And what will come after.

(Published in Cider Press Review)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)